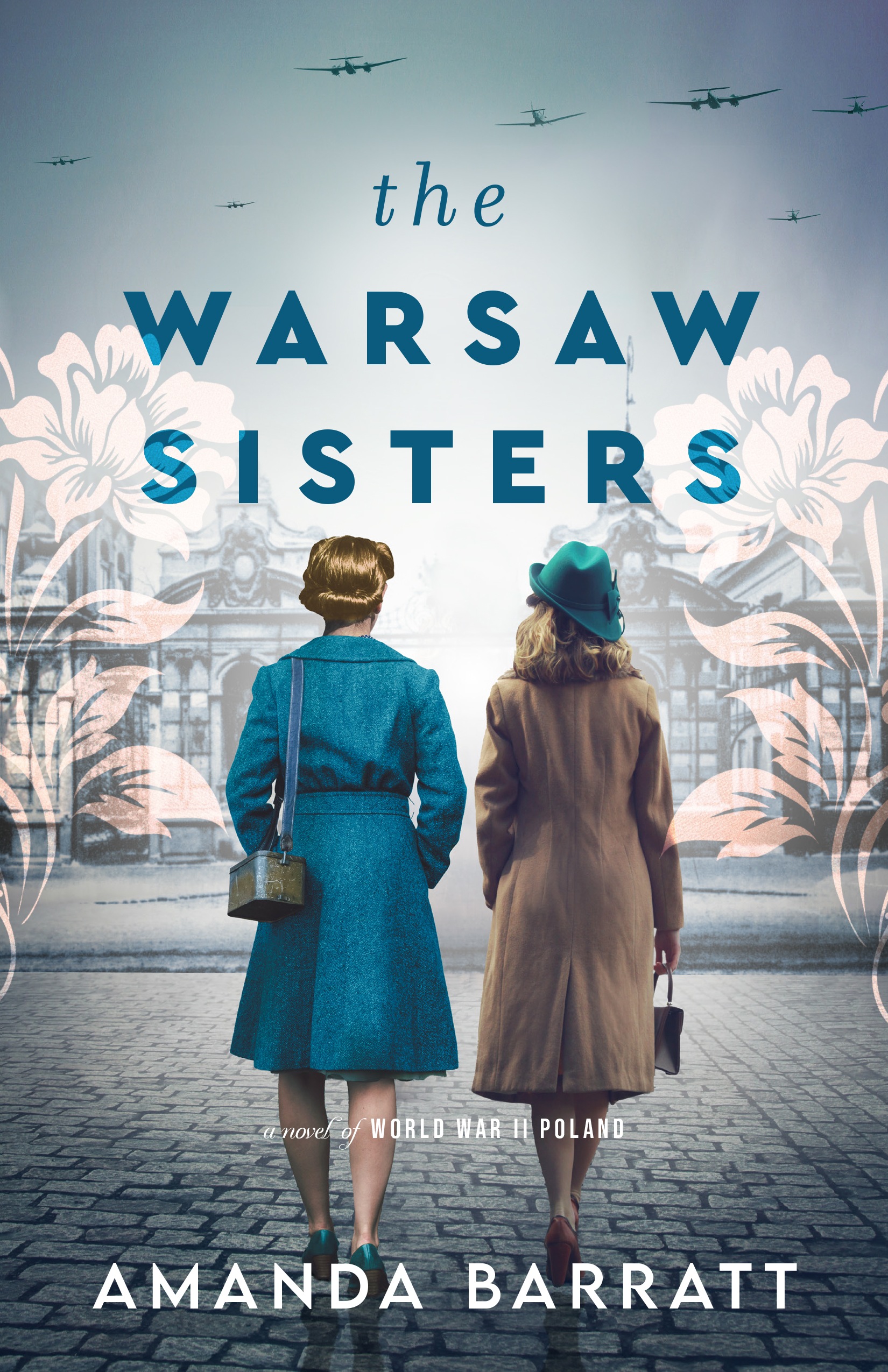

The Warsaw Sisters

Excerpt

Chapter One

ANTONINA

AUGUST 31, 1939

WARSAW, POLAND

Antonina-and-Helena.

That was how I remembered our names. Spoken in a single breath, always blended together.

Antonina and Helena. Helena and Antonina. Two lives braided into a single strand. A tie as certain as the ground beneath our feet and the air flowing through our lungs.

A bond that would remain immutable even as we watched our father go off to war.

For war would come to Poland. Few remained in doubt of it. Only the delusional, or the desperate, clung to the unraveling hope of peace.

I wasn’t delusional. But weren’t we, all of us, a little desperate? Maybe desperation bred delusion as we sought assurance that the ordinary would remain unbroken. That nothing would happen in the end. That the rumblings would die away, after all. We told ourselves and each other and kept telling ourselves because who, in spite of the flush of patriotism and bravado, could reckon with the alternative?

I stilled in the doorway of the bedroom. Beside the bed, Tata stood, his back to me as he fastened his rucksack. I stayed where I was, taking him in, gathering the moment close. The constancy I always found in his presence without him even speaking a word. His hands, steady and methodical, as they secured the rucksack. The way morning light touched his profile, outlined his uniformed shoulders.

He turned, caught sight of me. “Tosia.”

I gave a little smile, abashed to be found hovering in the doorway like a child, and crossed the room. “I wanted to see if there was anything you needed.” My fingers brushed the rucksack on the bed, the lumpy canvas out of place against the cream-hued counterpane.

“I think I have everything just about sorted.”

“Good.” I paused, trying to look only at his face and not at the uniform that transformed him from an attorney in a pressed suit to an officer in the army. He’d served during the last war—not the Great War, he hadn’t been old enough then—but the one that followed, between Poland and the Bolsheviks. Helena and I hadn’t been born yet; our parents hadn’t even been married. Tata returned in 1920, the Bolsheviks defeated, the independence of the infant Republic of Poland established. I’d glimpsed his old uniform hanging in the back of the armoire and seen the earnest young man in the photograph taken before he left, but neither had prepared me for the reality of him in uniform, as if time had unrolled backward twenty years, to another war and a younger man.

Silence lay between Tata and me. I didn’t know how to fill it, what to speak, what not to speak. The women of the previous generation were no strangers to sending their men off to war.

I’d had no practice. Not yet.

He paused, drew something from his pocket, held it in his palm a moment. “Your mama gave me this the day I left. The first present I ever had from her. When she found out I would be leaving, she came straight away, didn’t even stop to put on a coat. I can still see her, so young and lovely, her cheeks bright, shivering as she insisted she wasn’t cold. Stubborn as ever. Quite like someone else I know.” He gave me a pointed look and chuckled.

I tried to laugh, but it tangled in my chest.

“We stood in front of my parents’ house, and she unfastened the chain from around her neck, placed it in my hand, and told me to keep it safe.” His mustached mouth softened, his gaze far away. “I suppose that must have been the moment I realized she cared as much as I did.”

He’d told us the story when we’d been young, but never quite like this. Then it had seemed a scene out of a novel, the heroine bidding farewell to her sweetheart before he marched into the glory of battle. How romantic I had thought it. For it had been only a story, a glossy reminiscence.

It had not been real then.

He pressed what he held into my hand, the small oval still warm from his touch. The medallion he always carried, the tarnished silver engraved with the image of Christ. “I want you to keep it now, while I’m away.” He swallowed, and it twisted something inside me, such a look on my father’s face.

I inhaled a breath. “We’ll be fine. I will look after Helena. And Aunt Basia will be here.” She’d come last night to say goodbye, for they couldn’t spare her at the hospital today. Throughout our growing up years, our aunt—Tata’s only sibling and a respected physician—had reared her twin nieces as if we were her own, filling the place of the mother who died when my sister and I were scarcely a year old.

“Yes.” He nodded. “Basia will be here. I am glad of that.” He gave a brief smile. The same one he’d worn last night when we packed his belongings and he said he wouldn’t need much because he would be back soon. Then, as now, I read in his eyes what he did not speak.

Tata—so strong and steady—was afraid.

I did not let him know I knew this. Or that I was too. Our fear remained unvoiced, its presence thickening the air between us. It wouldn’t do to speak of such a thing, not at a time like this.

He’d spent the years sheltering my sister and me, making our lives safe and good and beautiful. Now I wished I could protect him as he had shielded us.

I wished . . . but I could not.

So I would give him what I could in these last moments together.

The memory of his daughter, steadfast and smiling. And he would know he did not need to fear for us and that we would be here.

Waiting, until he returned.

HELENA

AUGUST 31, 1939

There were no memories before him. He was my first and part of all the ones that followed. Drifting asleep to the sound of his voice spinning tales of mountains of glass and princesses in distant towers. My hand tucked in his as we walked to school, the September morning crisp, my heart beating fast beneath my coat. His rumbling laughter blending with crackly records as he taught Antonina and me to dance. His arms solid and comforting as I sobbed because the boy I’d secretly been fond of had begun a flirtation with one of my prettier schoolmates. My father’s voice gentle as he told me that I did not need to change to be loved, that the right man would prove himself worthy of my heart, not the other way around, and that I would always be his kwiatuszek—his little flower. The days working side by side at his firm, him meeting with clients in his office while I managed his appointments and typed his correspondence.

For as long as I could remember, he had been a constant in my—our—world.

Now a different world lay before us.

Sunlight warmed my face as we stepped onto Marszałkowska Street, the broad thoroughfare lined with edifices of stuccoed brick, shops and cafés with brightly lettered signs and elegant awnings, squat domed advertising pillars and slender iron lampposts, manicured trees planted at intervals. Red trams glided along the rails embedded in the cobblestones, automobiles and taxicabs sped up and down the street, carts and droshkies clattered and clip-clopped, bicyclists rode past, and pedestrians thronged the sidewalks.

In recent days, Warsaw sizzled, an electric current pulsing faster, faster. Passersby no longer walked, much less strolled. They hurried, rushed, strode, as though driven by wind at their backs, every step one of purpose, nearly all carrying the now-ubiquitous gas masks. Women hastened along the sidewalk, laden with shopping bags and baskets, expressions agitated, almost hunted. People sought to lay hold of what provisions they could, fearing shortages. Last month, at Tata’s advising, we laid in a supply of tinned goods, dried peas, kasza, sugar, and coffee. We bought no flour, for it might grow musty if stored too long. Four days ago, we’d gone to the shops and found them alarmingly sparse, no flour to be sold.

How could it be that only a few weeks ago all had been ordinary, the storm clouds gathering, but yet in the distance? Over the years we’d read the papers and talked of foreign politics, of Germany and Adolf Hitler, hailed as Führer by his adoring people as he regenerated a country crippled after the Great War and the Treaty of Versailles. Somehow it all seemed far off, removed from our lives in Poland. Troubles happening “somewhere else.”

But as Germany annexed Austria and then occupied Czechoslovakia, the storm swept closer. Closer still as Hitler issued demands to which our government staunchly refused to cede, among them the return of Danzig—a major port on the Baltic coast and a free city under the Treaty of Versailles. Only a few days ago, we had listened, stunned, to the announcement over the radio that Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a nonaggression pact, the two countries, once bitter foes and agelong enemies of Poland, agreeing not to make war against the other.

In that moment, a memory had surfaced. I had come into the sitting room one evening, just as Tata rose and turned off the wireless, Hitler’s fiery oration reverberating in the silence. He had turned to my aunt, sitting on the sofa, and said with a look I had never forgotten, “When a man is a fanatic, he is capable of anything, and that man Hitler is one of the greatest fanatics I have ever heard.”

The years had tested my father’s words, but only time would prove their measure.

Tata hailed a taxicab and asked the driver to take us to the Main Station.

War had not even begun, but already it had left its mark upon the city. Almost every window of the buildings we passed bore a pattern of thin white strips of paper, ours no exception. The newspaper said would protect the panes from shattering due to the vibration of nearby explosions and thus safeguard against injury from flying glass. I wondered if it had ever been put to the test.

Posters on walls and advertising pillars announced a general mobilization of our army. Amid the mobilization sheets hung a different poster. This one depicted a swastika from which an enormous hand seemed to sprout, bony fingers reaching, almost encircling a map of Poland. A Polish soldier stood in a warrior’s stance, bayonet fixed, poised to plunge the blade through the grasping hand.

Why had the artist rendered such a large hand compared with the height of the soldier?

Though the sun shone bright, I shivered.

We reached the Main Station, and the taxicab stopped. As we made our way into the station, I kept glancing at Tata, distinguished and somehow strange in his crisp tunic and peaked cap with its Polish eagle badge. He had been a soldier once, and with the mere act of the uniform mantling his shoulders, he returned to that part of himself again, as if a soldier was something one donned instead of became. But I could not admire him in military dress, no matter the chorus ringing out as men marched past, voices lusty.

“War, oh war, what a grand lady you must be, that you are being followed, that you are being followed by such dashing fellows.”

There was nothing dashing about a man leaving his home, his family, without knowing when or if he would return. Though, of course, he must go. Of course he must fight, if necessary. Perhaps I should have been filled with pride as my father left to defend our country, but my chest tightened so I could not tell if I was proud, only afraid.

The station swelled with men, youths who barely looked of age shoulder to shoulder with the more mature. Some boisterous, mingling with comrades like schoolboys setting off on an excursion to the zoo, others somber and silent, staring down at their feet or into the distance. A couple embraced, holding each other for a long and quiet moment. A woman waved a handkerchief in a gloved hand, calling out, “Goodbye, see you soon,” though to whom it was impossible to tell. Loudspeakers echoed, announcing boarding calls. The air was thick with heat and cigarette smoke and the unknown.

As we wended through the swarming multitude, I suddenly wished I could cling to Tata’s hand as I’d done when I was a child, his broad palm enfolding my fingers, an anchor when the world felt so very great and I so very small. But I was eighteen, a grown woman, and so I must make my way on my own.

When we reached the platform, he set down his rucksack. Antonina stood beside me, an emerald hat slanted over her reddish-gold curls, her features serene. But the rigid set of her shoulders and the way she clutched her handbag betrayed her inward struggle. I bit my lip hard.

Since the moment I glimpsed Tata’s mobilization orders—who could imagine one could hate and fear a simple white rectangle so much—I’d steeled myself for this parting. Told myself I would not break, nor even crack.

For long seconds, he stood, gazing at the two of us. “Take care of one another for me. Hold the other close.”

“We will.” I looked back at him steadily, gathering his face into the folds of my memory, wanting to remember for this and every moment until he returned.

“That’s how I can leave you this way. Knowing you’ll be together, no matter what comes.”

“You’re not to worry about us.” Did Antonina hear how her voice caught at the end? Did Tata?

“I’ll be home soon.”

Of course. Of course he would be.

He opened his arms and pulled us close, my sister and me. Crushing us against him, his breath tickling my ear, my own snatched from my lungs with the strength of his embrace.

“My beloved girls,” he whispered. “My Tosia and Hela.”

He drew away.

“I love you.” I smiled, forcing out the words through the swelling ache in my throat.

How fragile they sounded. They weren’t enough. How could they be? He shouldered his rucksack, met our eyes, the tenderness in his unraveling me piece by piece.

Then he turned away, faded into the crowd, one in a mass of uniforms. I blinked hard. Though tears burned, they did not fall. I should have been proud of myself for staying strong. But I wasn’t. Not really.

Time lengthened as we stood side by side, our shoulders brushing. The whistle gave a piercing blast, and the wheels of the train began to turn, slowly at first, then gaining speed. The faces of the men filling the windows passed as shadows, blurred by the rise of steam. I wanted to push forward, try to catch one more glimpse of Tata, but the crowd pressed too tight and the train passed too quickly until all that remained was the echo of the whistle and the people left behind.

Excerpt taken from The Warsaw Sisters © 2023 by Amanda Barratt. Published by Revell Books. Used with permission. May not be excerpted or distributed without the express written permission of the publisher.