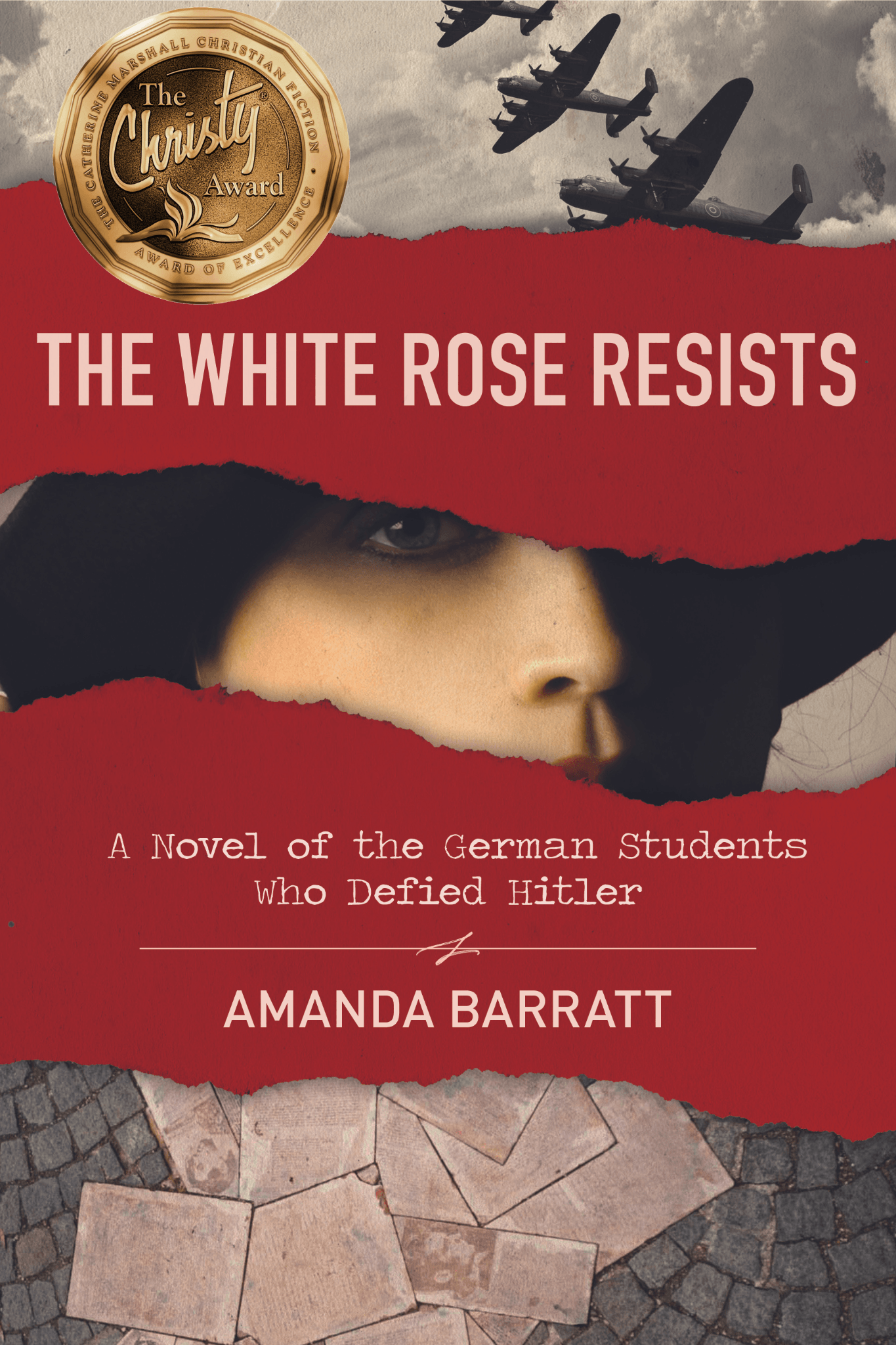

The White Rose Resists

Excerpt

Chapter One

Sophie

May 1, 1942

Munich, Germany

My future is waiting, a spark in the distance burning steadily brighter as the train approaches the city.

Scrunched into a window seat near the back, I fix my gaze on the smudged glass, my reflection an overlay. To some, the outskirts of Munich aren’t what could be called beautiful, but to me they are. Perhaps it’s simply because they’re new. New, after so many months of bleak sameness.

As we near the Hauptbahnhof, the sprawling patchwork of the city comes into view, the skyline dominated by ancient churches with spires seeming to pierce the skies, the twin cupolas of the Frauenkirche soaring high above them all.

But even now, as the train carries me toward my new life, longing twinges through me for Ulm, the city of my childhood.

On the rack above rests my suitcase and, beside that, a satchel packed by Mutter last evening. Her face flashes before me, graying hair piled into a wispy bun, apron wrapping her waist, and eyes intent on her task. I came into the tiny kitchen and found her adding a large kuchen to the bag on the counter.

“Where?” Since the outbreak of war, such confections are a rare treat. She turned with a smile I could tell was bittersweet.

“I’ve been saving rations for weeks. You only turn twenty-one once. And I want you to have the best of birthdays, my dear daughter.”

I hugged her. A goodbye embrace. Not only to her, but to the last vestiges of childhood. She smelled like fresh bread and soap. Frail though she is, she hugged me back with surprising fierceness. As if something innate tells her we will not see each other again for some time, and that when we do, much will have changed in me.

“Danke, Mutti,” I whispered against the soft cotton of her blouse.

The memory fades. Smoke belches from the train, the whistle blows. I scan the blur of forms and faces on the platform as the train pulls into the immense brick station. Hoping, knowing Hans will be waiting for me.

The train jolts to a stop. I stand on legs that shake from the motion of the train and, I admit, a touch of giddiness. I grasp my well-worn suitcase in one hand, satchel in the other, and join the queue of passengers waiting to disembark. The narrow corridor is rife with the scents of too many bodies packed together—sweat, stale cigarettes, and someone’s cheap perfume.

I descend the train steps, feet shod in sensible brown lace-up shoes, and draw in a breath of warm, slightly smoke-hazed air.

The station is flooded with light, echoing with conductors calling out departure times, the brisk footsteps of travelers. An officer in crisp Wehrmacht gray catches sight of a young woman expectantly scanning the crowd and hastens toward her. A cry of delight. A kiss. A trio of soldiers stride toward the exit, duffel bags slung over their shoulders.

I stand off to the side near a board listing train fares and schedules, everyone certain of their destination, it seems, but me. The daisy in my hair, fresh this morning, faded now, droops lower, petals tickling my ear. The weight of my suitcase sends an ache through my arm. I swallow, glance both ways.

He’ll come. Of course he’ll come.

Then it all fades. Hans strides jauntily through the crowd. No longer does the vast city seem to gulp me in and swallow me whole. Hans is here.

With him, Munich is, will be, home.

I drop my bags and throw my arms around him. My brother, so dashing, so tall, hugs me back, then puts me from him, his warm, strong hands still in mine.

“You’ve arrived at last.” He grins down at me, brown eyes twinkling. “It’s taken long enough.”

It isn’t the train he refers to. I’ve wanted to attend Ludwig Maximilian University with Hans since passing my Abitur. But first I had to do my duty for Führer and Fatherland and complete a term of labor service, which ended up turning into a two-year ordeal before I was pronounced able to start my studies. Hans has been privy to my frustrations from the beginning, and the twinkle in his gaze seems to say: It’s all behind us. The future is ours.

He grabs my suitcase and satchel. It’s then I notice Traute Lafrenz lingering in the background. My brother’s girlfriend watches us with a half smile. Everything, from her stylish gray suit to the jet-black curls brushing her shoulders, suggests a cosmopolitan elegance I could never hope to attain.

“Welcome to Munich, Sophie.” Traute smiles and embraces me warmly. “It’s good to see you again.” Her Hamburg-accented voice is rich and slightly husky, not in a seductive way, but like a girl who isn’t afraid to laugh often or cheer her lungs out at a sporting event.

“And you,” I reply. “You look well.”

Hans turns to us with a broad grin. Curling strands of dark hair fall over his forehead. “Ready, ladies?”

We nod and he falls into step between us, one arm looped through mine, the other through Traute’s, our threesome leaving the station behind, merging into the crowd. For a glorious instant, I’m here with my beloved brother on the cusp of the world, and I forget about the grueling years of labor service, about my anxiety for Fritz, even about the war. Warm air stirs my hair against my cheeks. Munich bustles with streetcars, pedestrians, buildings of stucco and stone rising high.

A flash of red catches my eye. Flags hang at intervals from buildings along the street. Reality floods back, smacking me like a storm-tossed wave. In Munich, I’ll never have the chance to forget.

The sea of black and scarlet will always be near to remind me.

Gruesome spiders drenched in blood.

***

Hans’s flat is, putting it kindly, what one would expect of a bachelor who doesn’t have his mutter around to pick up after him. Books and papers piled onto a round table probably meant to be used for dining. Unemptied ashtrays. A coat with worn-in elbows tossed over the back of the lumpy sofa. Even Hans’s prized modern artwork hangs crooked on the walls, prints by artists like Franz Marc, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky—bursts of color in the otherwise dingy student apartment.

The Nazis are firm in their insistence such artists are degenerate. Whatever doesn’t suit the Führer is always dubbed by that term. Degenerate art. Degenerate swing music, books, authors. Degenerate humans—Jews, Poles, the mentally handicapped. A familiar knot twists my stomach.

Settled on the sagging sofa, I cross my legs and watch Hans and Traute rummage through my satchel. We’ve spent the past hour chatting, sharing family news, and catching up. Hans and Traute kept their arms around each other the whole time. I’m happy for my brother. Traute is lively and intelligent, a medical student like Hans. Though with his record of past girlfriends, I can’t help but wonder how long this one will last.

Traute pulls out the bottle of wine, brandishing it aloft. “Tell me, Hans, do any of your other sisters want to celebrate a birthday in Munich?”

Hans laughs, holding up the kuchen and inhaling its rich, buttery scent.

Seeing them together makes me long for Fritz. Leutnant Fritz Hartnagel, my fiancé. We exchange letters, as do so many couples separated by war. But pen and paper aren’t the same as sitting in some sun-drenched spot in midsummer, his whisper in my ear, and my head against his shoulder. There’s no denying that.

“The rest of the party will be here soon.” Hans ambles over and sits on the edge of the armchair.

“Party?” I ask.

“Of course.” Hans grins. “I wouldn’t dream of marking this momentous occasion without a party for your birthday. I invited some friends, the ones I’ve told you about.”

I gasp. “You mean Alex and Christl and Kirk?”

Hans nods, looking pleased. “I can’t wait for you to meet them.”

“You won’t have to wait long,” Traute calls. “I hear them coming up the stairs.”

Instinctively, I tuck my hair behind my ear (I’ve since plucked out the faded daisy) and smooth my navy dress. I’ve never put much stock in my appearance, save to bob my hair in a daringly boyish cut during my teens. But I might start if I spend much time around the pulled-together Traute. Like all proper German girls, her face is bare of cosmetics, but her fine cheekbones and dark eyes need no accentuation.

A knock sounds on the door, and Hans rises to open it. In an instant, the room is bursting with three young men, all exchanging hearty handshakes and greetings with Hans and Traute.

I stay where I am, on the sofa, watching the scene. The three arrivals fill the room with their broad shoulders and deep voices, an unmistakably masculine presence. I’ve missed being around young men. Much of the past two years have been spent in the company of dimwitted girls my own age or kindergarten students and fellow female teachers.

“Come here, Sophie.” Hans motions me forward. Their gazes fix on me. So this is Hans’s little sister, they must be thinking.

I cross the room and stand next to Hans. “Sophie, meet Alex Schmorell, Christl Probst, and Kirk Hoffmann. Everyone, my sister, Sophie, arrived in Munich at last.”

Lanky, blond-haired Christl is the first to step forward. His smile is gentle and warm, as is the handclasp he gives me.

“We’re so happy you’ve joined us, Fräulein Scholl.”

“Please, call me Sophie.” My smile is easy.

“Very glad to meet you. Hans says you’re enrolled at LMU for the summer semester.” Brown-haired and broad-shouldered, Kirk has the look of one who makes feminine pulses flutter while being oblivious to it. His welcoming grin and strong handshake endear him to me instantly.

“Ja, and I can’t wait to get started.”

“At long last we meet the famous Sophie.” Alex takes my hand, but he doesn’t shake it. Instead, he bows low, reddish-blond hair falling into his eyes, lips grazing my skin. When he looks up, there’s a twinkle in his blue-gray gaze.

“I feel as if we already know each other, Hans talks about you so often.”

“All good things, I hope.” His mouth tilts in a sideways grin.

Unlike the others, who wear suits, a coffee-brown turtleneck sweater encases Alex’s shoulders. His voice has a cultured quality, with intonations that mark him as not altogether German. Hans has told me of Alex’s Russian heritage; he’s the son of a German vater and Russian mutter, the latter who died before Alex’s second birthday. Alex lived in Russia until he was four, when his vater took him and a Russian nursemaid back to Germany. Yet Russia remains the land of Alex’s heart, and he was never more grieved than when our country invaded his.

“There’s another grand thing about Sophie. Along with her lovely self, look what she brought us. Wine and a birthday kuchen.” Traute brings the kuchen from the table, Hans, the wine. They place both, along with plates and glasses, on the low table in front of the sofa. Traute claps her hands. “Gather ’round, everyone.”

The young men waste no time. Traute settles on the sofa, along with Hans. Christl takes the armchair, and the rest, the floor, sitting cross-legged on the carpet near the table. The casual atmosphere loosens the tension between my shoulders, almost unrelenting since the day I started labor service.

“Do the honors, Sophie.” Hans slips his arm around Traute, and she leans her curly, dark head against his shoulder.

“Your birthday is soon?” Christl asks, as I move to cut the kuchen.

“Ja, my twenty-first. On the ninth.” I cut and plate generous slices of the brown, sweet-smelling confection.

Once everyone has been served, Hans lifts his glass. “Everyone, a toast. To Sophie. May she have the happiest of birthdays, enjoy her time in Munich to the fullest, and get high marks on every exam.” He winks at me.

“To Sophie,” the group choruses with lifted glasses.

“Danke.” I smile, sipping the fruity, earthy wine. I settle on the floor beside Kirk, smoothing my skirt over my knees.

“Mmm. Wonderful.” Traute dabs the corners of her mouth with a handkerchief. “You must take a piece home to Herta, Christl.” To me, she adds. “Herta is Christl’s wife. They have the two sweetest little boys.”

“I actually can’t stay long. I haven’t seen them much lately and promised to tuck them in.” Christl sets his glass on the table, a look of deep fondness in his eyes. As if, even now, he’s not with us, but in some lamp-lit bedroom, kissing his little sons’ fresh-from-the-bath hair and reading them a bedtime tale.

“I hope I have the chance to meet them sometime.” The kuchen is sublime, buttery and rich. I savor another bite.

“You will.” Christl smiles, his words as genuine as if it’s already done.

“So what do you think of Munich, Sophie?” Kirk turns to me.

I hesitate. Honesty is not a virtue in the Germany in which we live. Unless one’s honest opinions align with the Führer’s, of course. But these are Hans’s friends. I trust him enough to know he would never add someone to his close circle who didn’t share our beliefs.

Plate balanced on his knee, Alex swirls the wine around in his glass. The reddish liquid reminds me suddenly, uncannily, of swastikas rippling blood-red in the wind.

How long has it been since I’ve been able to give free vent to my feelings, trusting that no ideology-tuned ears are within range? Too long.

“Red and black everywhere.” I meet Kirk’s eyes, sensing the gazes of everyone upon me—these bright young university men. “There’s not a great building in the city that isn’t plastered with one of Hitler’s symbols. It’s disgusting, scars on our beautiful architecture. Of course, Ulm isn’t much different.”

“I wonder how long before it becomes our symbol of defeat, instead of victory?” Alex sets aside his half-finished plate as if he no longer has an appetite.

“That”—Kirk’s tone is quiet, but distinct—“depends on the people.”

Alex’s eyes, twinkling moments ago, now blaze with inner fire. Looking into them makes me start. Embodied in their depths is a passion the whole army of Hitler’s goose-stepping minions, puffed up with propaganda, can’t match, much less quench.

I cannot tear my gaze away.

“It’s our fault, you know.” Our casual circle seems to shrink, until we’re leaning forward, hanging on Hans’s words. “We’ve allowed ourselves to be governed without resistance by an irresponsible faction ruled by dark instincts. Worse than children. Children, at least, sometimes question their parents’ decisions. But have we questioned? Nein, we’ve let ourselves be led like dogs on a leash, panting after Goebbels’s every speech, Sieg Heiling like trained monkeys.” My brother spits out the words.

Christl nods. “Yet some have spoken out. Bishop von Galen, for example.”

“Who’s reading him?” Darkness creeps through the window, a shadow falling on Alex’s features. Soon, it will be time to draw the blackout curtains. “He preached three sermons, which a few brave souls dared to duplicate, resulting in a few hundred copies, likely little more. That’s not enough. Germany has been allowed to nap in the middle of carnage. It’s time to wake up, for this country to rub its eyes and look around and see the truth.”

Christl glances up. He’s no longer the gentle family man, smiling at the mention of his little ones, but a revolutionary with a fervor Goebbels, no matter how many stupid speeches he gives, could never emulate. His hands draw into fists. “It’s not just ‘this country.’ It’s our country. When this madness has ended, those who are left will be judged by the world, no matter what they thought amongst themselves. It’s action that will stand the test. Only action provides absolution.”

The words remain in my mind long after the men leave for their lodgings. I stand at the window, peering through a crack in the stifling blackout curtain, the evening chill soaking into my bones.

“Only action provides absolution.”

Excerpt taken from The White Rose Resists © 2020 by Amanda Barratt. Published by Kregel Publications. Used with permission. May not be excerpted or distributed without the express written permission of the publisher.